This post was originally posted on Substack. That platform does not align with my values so I have copied it here instead. If you have subscribed to my Substack, please move your subscription to here.

Welcome to the December 2024 FloodSkinner newsletter.

As I look back and reflect on the last year, the one big thing it has taught me is that life can come at your fast. Personally, our family has experienced extreme lows and extreme highs over the last year, even within a day or two of each other. For both good and bad, our lives have been turned upside down.

Significantly, my wife landed her dream job and with it we made a move to beautiful York. We have always dreamed of living in an historic European city, somewhere like the cities we love, Prague and Ljubljana, and I think we have found the closest we’ll get in the UK. I would not have imagined this time last year that we would be here but I love it.

It has been a busy year professionally too. Some of my highlights are:

As part of my role at the Environment Agency:

- Published our report on the potential and pathways for open methods in operational flood hydrology, produced by JBA Consulting. Read it here.

- Published reports covering a major survey of UK hydrologists I led. Read them here.

- Completed my three-year term as a trustee for the British Hydrological Society and co-chair of the Communications and Publications committee.

- Co-led the Environment Agency’s summer activities at the Science Museum. We led a team of over 120 volunteers who engaged over 80,000 visitors over four weeks. I won a local recognition award, and the team won the EA’s One Team award, for this project.

As FloodSkinner:

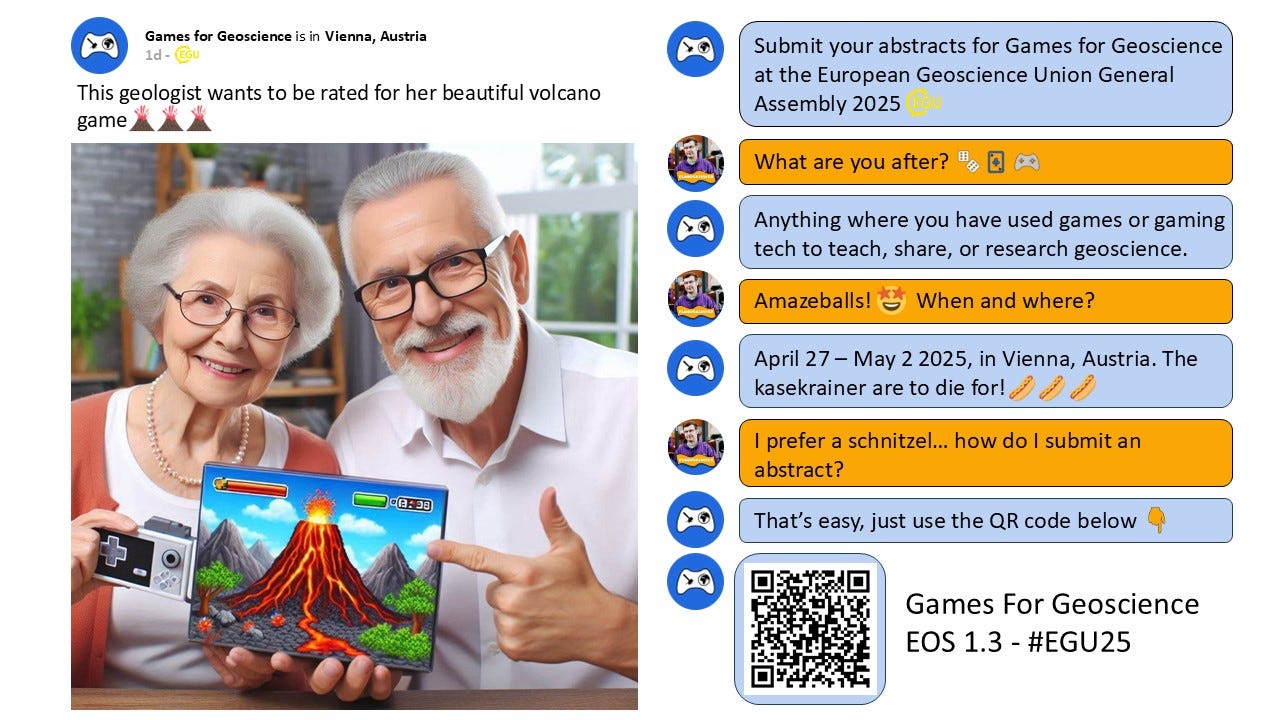

- Travelled to Vienna to convene the Games for Geoscience and Geoscience Games Night sessions at the European Geoscience Union General Assembly. I also contributed to the Elevate your Pitch short course.

- Presented an invited seminar on the history of SeriousGeoGames for the University of West England’s Science Communication Unit.

- Presented on Games and Models at the University of York’s Play for the Planet meeting. See my home recording of it below.

- Developed the Play your PhD workshop, inspired by Lego™ SeriousPlay™, and delivered it to the first cohort of students on the Flood Centre of Doctoral Training, University of Southampton. Find out more about my workshops and how to hire me here.

Being such a busy year, I admittedly have struggled to find the headspace to do some of the voluntary scicomm stuff I love, including making videos for my YouTube channel and delivering this newsletters monthly. You may have noticed it has changed a few times too as I have strived to find the most useful and interesting format.

I am still committed to bringing you the latest news, events, opportunities, and cool stuff from where games and the environment meet. However, I found most of the items on Twitter and as that platform is no longer an enjoyable space to be, I have deleted my accounts. I cannot find the same volume of information via BlueSky or LinkedIn just yet.

At the same time, I am beginning to spin up a few projects that I’d like to share. Consequently, the newsletter will become more of a hybrid of my own news and the Gaming Environments items. This will be distributed via Substack once again, with a shortened Gaming Environments newsletter shared on the Games for Geoscience newsletter.

Chris (aka FloodSkinner)

Adventures in Model Land

I am very, very excited to launch Adventures in Model Land! We use computer models to help us make decisions about the real-world. Models however can never perfectly recreate the real-world, having to make simplifications and compromises to operate and be useful. In this way, they create their own model lands. Erica Thompson’s brilliant book, Escape from Model Land, shows us how we must leave and understand these model lands to make good decisions about the real-world. But what if we could bring these worlds to life, explore them more deeply, and even undertake quests within them?

Adventures in Model Land is inspired by tabletop roleplay games (TTRPGs) to help those who work with computer models breathe life into the model lands they use. Level One, released December 1st, guides you through the world building process. We are looking for volunteers to test this framework by creating and sharing model lands for their own. Check out the draft framework here and contact me if you’d like to help.

In the future, we will launch Level Two to help you create quests for players that take place inside your model land, and Level Three, a guide to hacking existing games to play be the rules of your model land.

Finally, if you are attending the European Geoscience Union’s General Assembly in 2025, you can take part in the Into Model Land short course, based on Level One of the framework. Find out more here.

Adventures in Model Land has been developed by Chris Skinner, Erica Thompson, Liz Lewis, Rolf Hut, and Sam Illingworth.

New Paper

Work led by Katie Parsons, and co-authored by myself and Alison Lloyd Williams, has recently been published in Geographical Research – Using 360 immersive storytelling to engage communities with flood risk.

This interdisciplinary work brings together my previous work with VR, 360 animation, and immersive storytelling with SeriousGeoGames, Alison’s work using creative interventions to help flood-affected children and young people share their stories, with Katie’s expertise with flood education.

The paper details the work to create the Help Callum and Help Sali immersive flood stories, the co-production of teaching materials with children, young people, and teachers, and the evaluation of their efficacy as a resource. You can read it open access here.

Gaming Environments

Gaming Environments is the newsletter of Games for Geoscience. It brings you the latest news, events, opportunities, and cool stuff from where games meet geoscience and environmental research and action.

News

QUARTETnary by The Silly Scientist is an educational game about geological time. After it was successfully backed in a KickStarter earlier this year, it is now available on general sale. Get your copy here.

The winners of the first ever Playing for the Planet Awards have been announced. The Playing for the Planet alliance aims to help the gaming industry engage with environmental issues and the awards congratulate those who have made a significant contribution. Read about the winners on PocketGamer.biz here.

Issue 18 of Consilience, the journal that explores the spaces where the sciences and the arts meet, is available to read now here. The theme is ‘Consciousness’.

UNESCO and 8one Foundation have published a report on gender dynamics in games and gaming, globally. The Gender Equality Quest in Video Games is available to read now here.

Recent research by the University of Bolton, through the Game Realising Effective and Affective Transformation (GREAT) showed the effectiveness of engaging gamers with climate issues within games. They used in-game QR codes to engage gamers with climate-related surveys and compare clicks with traditional clickable adverts, finding in-game codes drove greater engagement. Read more here.

Events

The call for abstracts for the 2025 General Assembly of the European Geoscience Union is now open. The deadline for abstracts is January 15th 2025, 13:00 CET. You can find more details and browse the sessions here.

The Games for Geoscience session is amongst the programme. If you use games for communicating, sharing, teaching, or researching within a broad theme of geoscience, please do tell us about it. We also welcome work using gaming tech, including virtual and alternative realties (ie, VR and XR). You can submit an abstract here.

Opportunities

Do you write sole-play TTRPG? Want your game featured in a new bundle? You can submit them to the Solo but Not Alone bundle here. Submissions close on December 22nd 2024. The bundle will be released on January 9th 2025 for $10, with funds going to Take This, the gaming charity supporting people’s mental health.

Cool Stuff

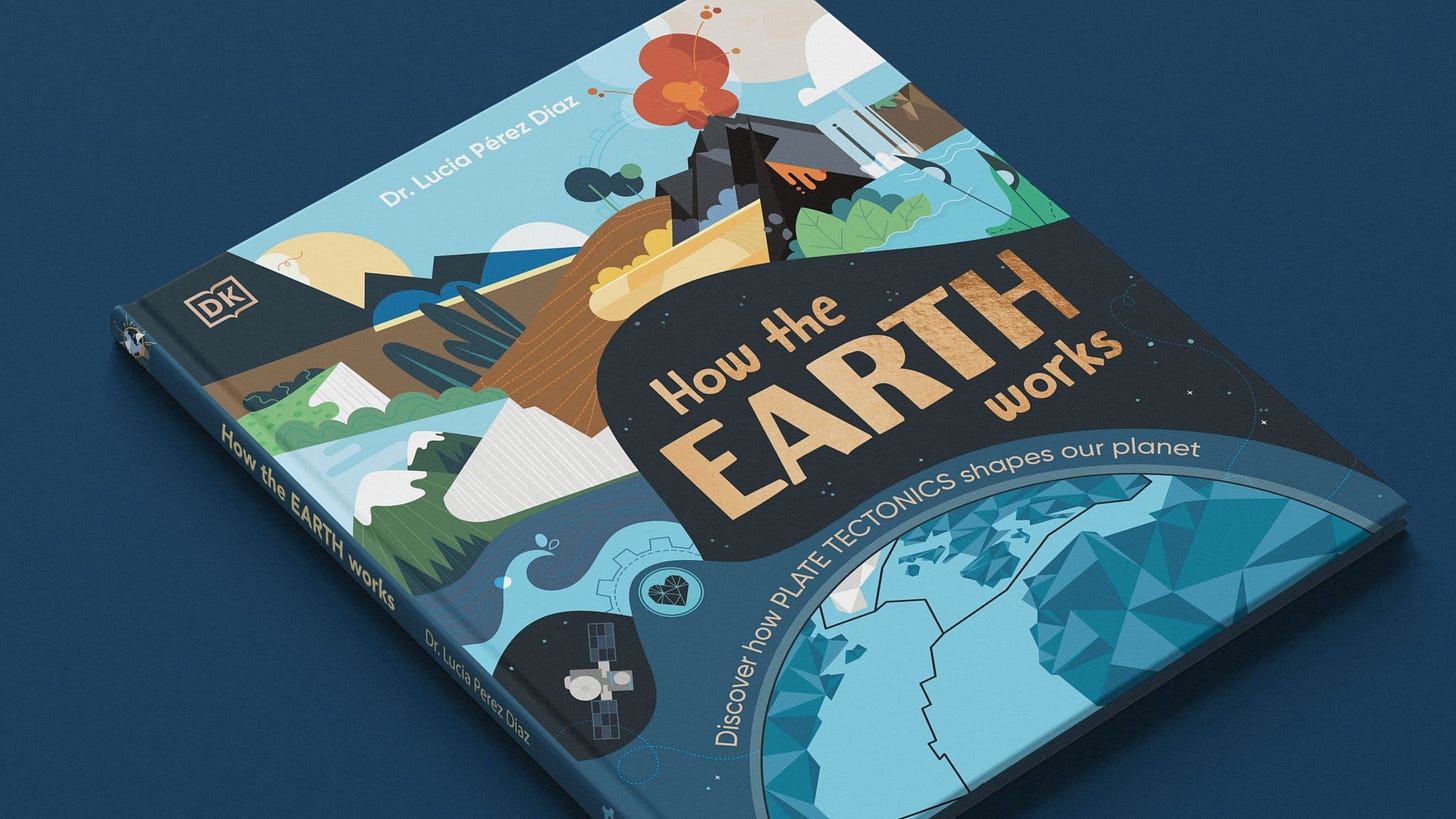

Awesome science artist, Dr Lucia Perez-Diaz is releasing her first science book aimed at children. And it looks gorgeous! How the Earth Works is published by DK Books, and “takes inquisitive 7-9 year olds on a journey of discovery into the inner workings of our planet. You can pre-order it here.

About this Newsletter

This is the personal newsletter of Chris Skinner, a science communicator and author under the name FloodSkinner. It includes the Gaming Environments newsletter that is also published on the Games for Geoscience website. It shares News, Events, Opportunities, and Cool Stuff from where games meet geoscience and environmental research and action. It is free and there is no paid tier. If you want to say thank you to Chris, you can ‘buy him a coffee’ using the link below.

Views expressed in this newsletter are mine and do not represent those of my employer. Content and links are provided for informational purposes and do not constitute endorsements. I am not responsible for the content of external sites, which may have changed since this newsletter was produced.