Back in 2019, at the peak of my work on the Earth Arcade, I picked up a board game called Photosynthesis. I am not a big board game player but I was attracted by its beautiful, and very ‘green’, aesthetic and its tactile tree playing pieces*. I was also drawn by its promising environmental messaging, with the publisher’s, Blue Orange, motto proudly stated ‘Hot Games Cool Planet’.

I also remember playing it with Amy. Each turn the sun moves around the board. You plant trees. Those trees collect light energy and cast shadows on other tree to stop them collecting energy. You use energy to grow your trees or plant new ones. You score by chopping grown trees down. We remarked how it was bizarre how you won an environmentally-themed game through deforestation but then thought no more of it. I went on to use the game as an example of an environmentally themes board game as part of my Earth Arcade Academy launch event.

Dr Chloé Germaine and Prof Paul Wake of the Manchester Game Centre think about games on a whole different level to most people. Certainly more than me. Recently, I was very happy to be invited to the University of York’s Environmental Sustainability at York (ESAY) by Director of Education, Prof Lynda Dunlop, to hear Chloé and Paul talk about their research. And Photosynthesis was right in the heart of their work.

Games can be broken down into their components: the mechanisms of the rules and systems that dictate how it plays; the dynamics of player inputs and decision-making; and the skin of aesthetics and story that add flavour to the game. They saw through the skin of Photosynthesis to what it was hiding underneath. It isn’t an environmental game at all, it is a war game and they were going to show it by peeling back the game’s skin and revealing its true nature.

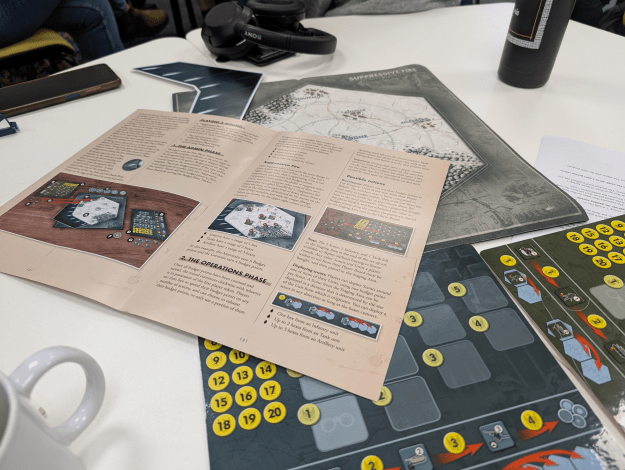

Chloé and Paul took the game back to its bare bones. They created a new narrative based on the siege of Bastogne during World War 2’s Battle of the Bulge. New artwork was commissioned for the board and all of the game assets. The rule book was reproduced but not rewritten – only names were changed. Suppressive Fire was created. Functionally, the game was completely unchanged yet visually it was unrecognisable. When they tested it alongside Photosynthesis, audiences preferred the deskinned version as the narrative fit the mechanism more comfortably.

The presentation taught me valuable lesson about the importance game mechanics. The way a game works, the decisions it compels players to make, are a huge part of what they take away. Assuming good faith from developers, the mechanics of their game will be leaving players having learned the wrong message. A pretty, green-coloured skin is not enough to make a game environmentally-themed, especially when it is rooted in a system that is creating the problem.

You can read more in Chloé’s chapter, Nature’ Games in a Time of Crisis, in Material Game Studies: A Philosophy of Analogue Play. More publications based on this work are in the pipeline and will likely be included in the Gaming Environments newsletter in the future.

What game would you reskin to give it an environmental aesthetic?

*The trees have been useful for my gaming imagery over the years…

This post originally appeared in the Imagination Engines newsletter. To read this content a few weeks earlier, subscribe to the newsletter below.