Welcome to August’s issue of Imagination Engines! Thank you for reading.

This summer I have been given a wonderful opportunity to develop a brand new module on River Management for York St John University’s Geography courses. I am so excited for this and have been loving designing the module and beginning to put the elements together. It’s hard work – fun hard work – and consequently I’ve had to reprioritise how I use my spare time.

It does not change my long-term goal of writing a book. In fact, I think the whole process is excellent practice and brings that goal closer. However, I need to temporarily change how I use this newsletter – I have been using it as a motivator to get me writing regularly and to explore different ideas, with 3-4 articles each month. I just don’t have capacity for this now but want to maintain a monthly publication schedule. Instead, I will focus on giving short updates on my main projects that are listed on the front page of my website.

Ongoing Research

I have a new paper out this month as a co-author. The work was led by my former supervisee, Josh Wolstenholme, and covers his PhD field work on the geomorphic change induced by the installation of leaky woody dams. It is a timely reminder that rivers move and change, especially if you stick stuff in them.

Adventures in Model Land

This is an open-source system to make game worlds based on the numerical models we use to learn about the world around us and predict the future. It is inspired by the world building used in tabletop roleplay games (such as Dungeons & Dragons) and just needs your imagination. You find out more and download the free guide here.

I’ve also started a Discord server for Adventure in Model Land as a place to discuss the system, share the game worlds you create, and to get help from others. Join it here.

FloodSkinner YouTube Channel

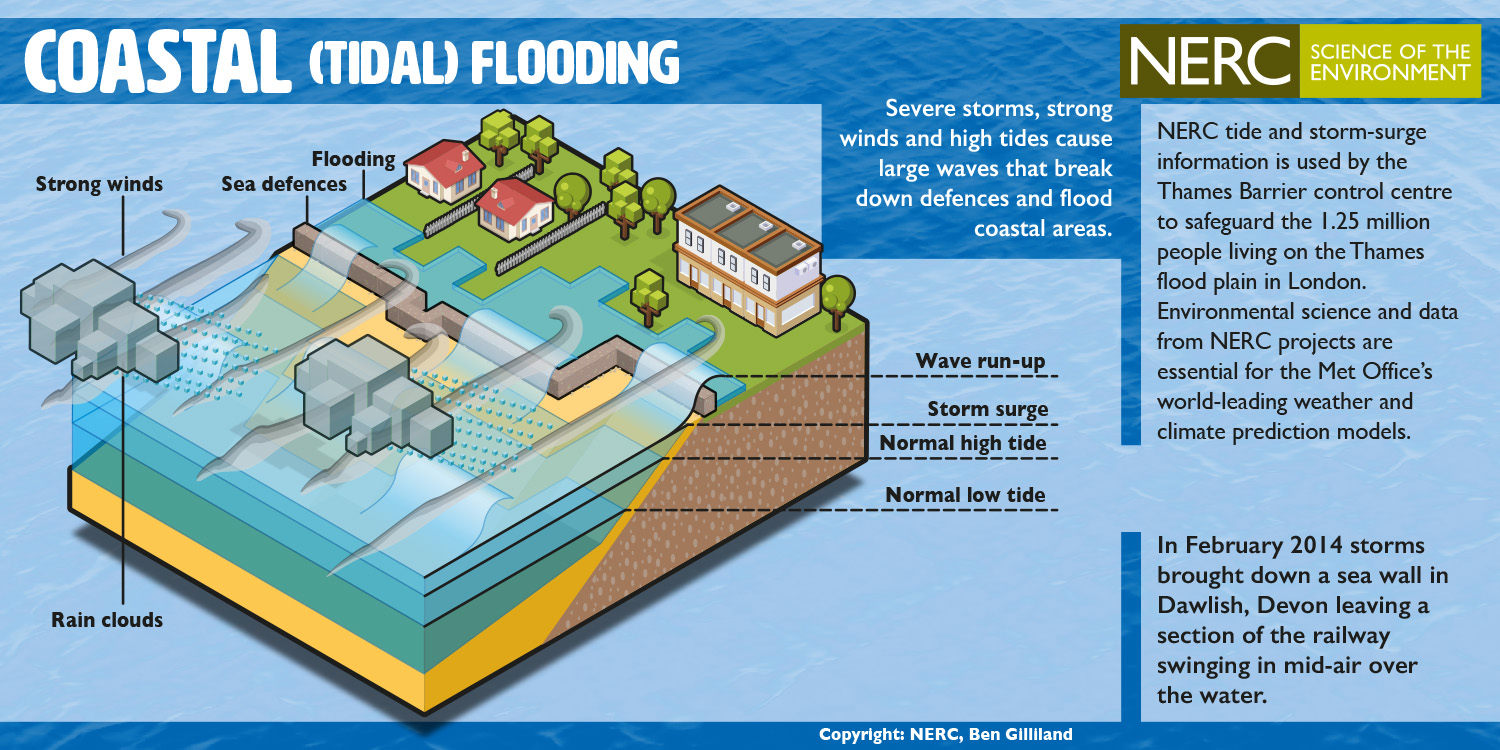

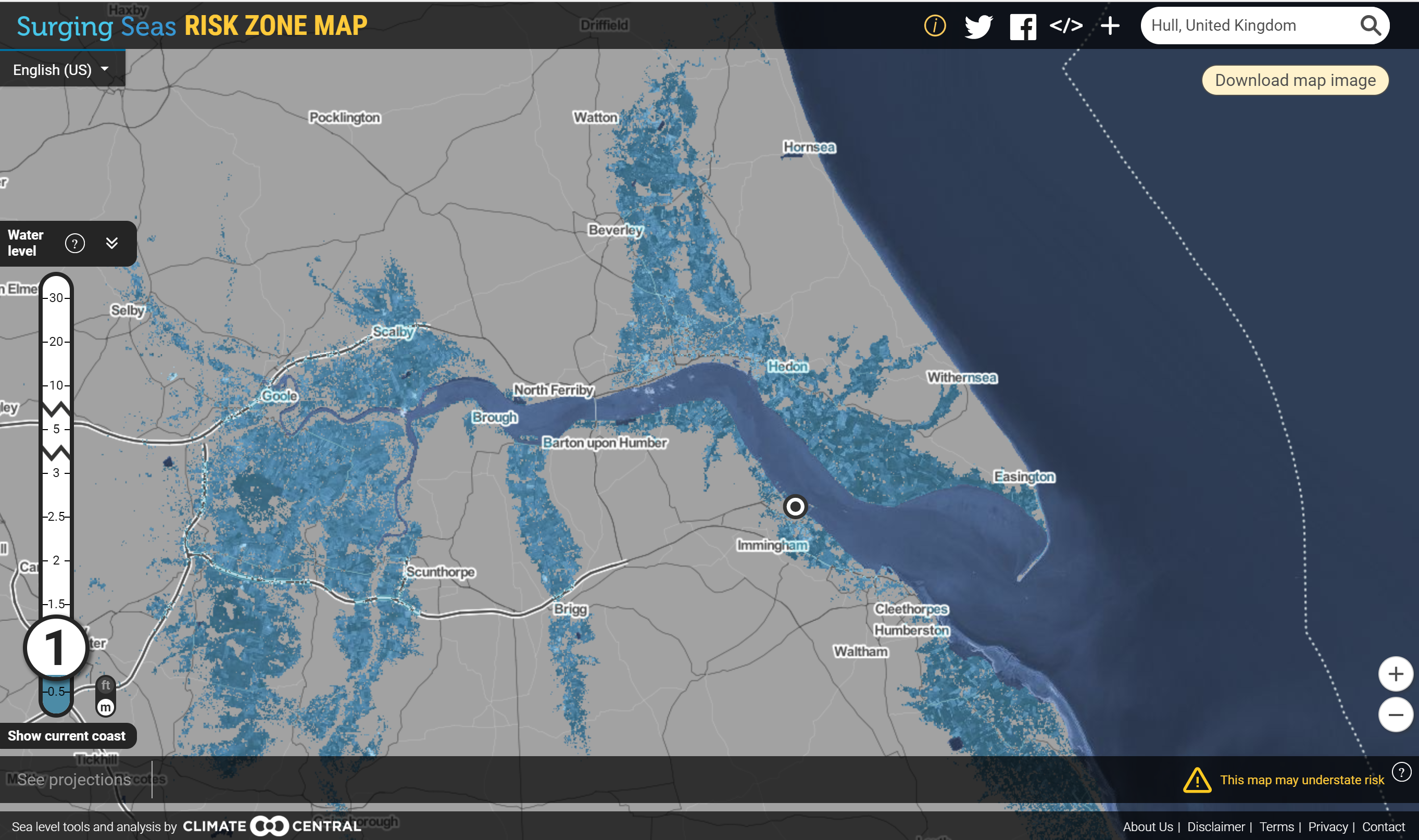

I had a new Short out in the last month. I came across some videos discussing rumours and leaks about the (long) upcoming Grand Theft Auto 6, including some indications it might include a dynamic weather system. The rumours suggest that the weather system would interact with the terrain and influence the game – it rains, water pools, and roads flood and become inaccessible.

This is obviously very exciting for me so I put my thoughts into a Short. I was short on time and cutting all the clips together was quite laborious – unfortunately I didn’t get chance to do a full set up and did not light my greenscreen properly, so this is a bit messy (the kitten also moved the screen partway through filming and messed it up more…). Despite this, it did moderately well, with >1,100 views.

Games for Geoscience

After the annual General Assembly of the European Geoscience Union (EGU), summer is pretty quiet for Games for Geoscience. With the call for sessions for the 2026 General Assembly now out, in the coming month I’ll be pulling the team together and proposing what would be the 9th Games for Geoscience session.

I still have ambitions to make it more than just an EGU event, with year-round activity and a community. If you’re interested, you can join the Discord server.

LEGO® SERIOUS PLAY®

In the last month I had the great pleasure of the supporting the Geography staff at York St John University with a LEGO SERIOUS PLAY inspired workshop. I was asked to support the department as they considered the best ways to support the future employability of their students and the creative approach of the workshop led to some valuable insights.

I’m looking forward to October this year where I will be returning to Southampton to once again deliver a Play you PhD workshop to the new cohort of Flood CDT students.

Project Prospero

Project Prospero is my hobby project where I am combining two pillars of geekdom into one nerdy-monster – a Warhammer-themed train set! The setting is the homeworld of the Thousand Sons Space Marine Legion, Prospero, as it is being pillaged by the Space Wolves Space Marine Legion. I am using models from the Legions Imperialis game and n-gauge tracks and trains. The centrepiece will be the giant pyramid of the Pyrae Cult, partially destroyed, using a Playmobil pyramid as its base.

This month I have been progressing the models and mocking up the layout to get some idea of scale. Because I don’t have space to leave out a layout, it will need to be fully modular. Check out a video I made from my mock up below:

About this Newsletter

I am Chris Skinner, a science communicator, STEM professional, and ADHDer. I am on a mission empowering people to unlock their full potential by transforming imagination into a powerful, actionable skill. This newsletter tracks my journey. I would like you to join me, so please subscribe. This newsletter is free and I do not offer a paid tier. If you would like to say thank you and/or help me in my mission please buy me a coffee using the link below.

Views expressed in this newsletter are mine and do not represent those of my employer. Content and links are provided for informational purposes and do not constitute endorsements. I am not responsible for the content of external sites, which may have changed since this newsletter was produced.